On a Monday night in early March, viewable through the front glass of the historic Globe Building in Pioneer Square, there’s a crowd so large it trickles out the door. If you arrive even slightly after the event’s 7:30 p.m. start time you won’t be guaranteed a seat – tonight, the venue is almost certainly over capacity. The overflow piles up in small crowds, huddled in coats and sharing something to smoke around a sandwich board whose crisp lettering succinctly addresses the reason they’re here: LIVE JAZZ.

This Romanesque Revival structure, raised over 125 years ago in the wake of the Great Seattle Fire, is the current headquarters of the Seattle Jazz Fellowship. I say “current” because the residence is both gratis and temporary – the organization, founded by musician Thomas Marriott in 2021 and dedicated to promoting and sustaining local jazz, is here until another tenant ponies up for the space. Until then, the Fellowship hosts its myriad shows on the ground floor of the building’s westmost occupance, in a room whose brick walls lend themselves aesthetically to tonight’s event.

Inside, those aged walls struggle to contain the energy. The crowd leans far younger than you’d expect at a public jazz show: plenty of teens and young adults are sitting up front, having arrived early enough to get a seat. Some are in the back socializing, some are outside hanging, but many others hold their full attention on the players, enchanted by the music. “It’s blown up,” a regular attendee tells me later in the night, as we peer out into the stuffed venue from backstage. “I remember three months ago when I used to be one of seven or eight people here. It’s crazy.”

Marriott appears at the top of the evening, a house band ready to play behind him. “If you’re here to sit in and play a tune,” he says, “we have a sign-up sheet in the back. The only requirement is that you play jazz.” This is the heart of the Fellowship’s Monday night jazz jam session: after the band – featuring scene regulars D’Vonne Lewis, Tim Kennedy, and Trevor Ford – breaks the ice with a handful of tunes, the rest of the night’s music is provided by voluntary audience members, many of whom have their own instruments slung over their shoulders, waiting for their turn to be called. One group launches into a steady rendition of Miles Davis’ “All Blues,” another is led by a talented jazz vocalist who, halfway through the tune, gently encourages their fresh-faced drummer to take a short solo. Jazz is far from the easiest style of music to play, but what could end up a mess of clunking rhythm and unpurposeful dissonance is instead a wondrous display of communal serendipity, at a time when pure communal experiences feel more important than ever.

Marriott, speaking to me the week after, agrees. It’s one of the reasons he gave the Fellowship its name. “Most of us who play jazz music do it for the spiritual rewards -- ‘fellowship’ being one of them,” he says. “We're not doing it for the money. We're definitely not doing it for fame and fortune. We do it for that feeling of being connected. But when there's no place to connect, then we don't have that, and that erodes so much of the music, the community, and everything that's required to sustain it.”

A Seattle native with ties to New York’s jazz scene, Marriott’s words about his hometown are far less than sanguine. “Our institutions of jazz have failed to represent the local community pretty much at every level,” he says bluntly before laying out his case: low wages, high rent, scarce opportunities to play, even scarcer opportunities to play for good money, and no dedicated venues in which the community at large can anchor itself have gravely hampered Seattle’s jazz culture.

The Fellowship’s solution, in brief, is to make their promotion of local jazz both accessible and affordable. Most of the events they hold, from individual performances to speeches from their artists in residence to their Monday jam sessions, are completely free to attend. You’re also able to attend a series of exclusive members-only events by donating $60 annually, a package undeniably attractive to a populace accustomed to receiving access to all recorded music for a handful of dollars a month. At the same time, the Fellowship pays its performers well – far better, according to Marriott, than the average. “A lot of the calculus that goes into writing budgets and whatnot is ‘What's the least amount we can get away with paying local musicians?’” he explains. “With the Fellowship we take this other tact: what's the most we can get away with? Because we find that that's good for the music. It's not just about putting money in musicians' pockets; it's about changing the way musicians feel about pay, about what they think that they're worth.”

At the same time, the Fellowship’s embrace of Gen Z has become its most effective marketing point. On top of making every event all-ages, the organization also offers a $25 annual membership for those under 21, and also routinely hosts an all-ages jam session on the first Sunday of every month. That, plus social media virality, is allowing the youth interest in the Fellowship to sustain long past the fad stage.

In the front row of tonight’s show, sitting in a warm striped sweater, is the reason for that virality. Michelle Villafuerte, a young jazz appreciator whose social media posts about hidden Seattle gems have earned her robust online and offline followings, started attending the Monday jams shortly after the Fellowship moved into the Globe Building in October 2024. “It wasn't packed,” she tells me. “There were seats filled, but it wasn't like how it is now.” The first videos she posted did numbers, and by the end of the year the attendance had exploded. So effective was her coverage of the event that, after Marriott discovered her posts, he personally offered her a lifetime membership.

“What's great about jazz music is that it is the past, present and future all in a single instant,” Marriott said. While the Fellowship has no problem attracting the “future,” it’s the “past” Marriott is currently concerned with.

“Honestly, I'm not sure local jazz musicians are really a fan of local jazz. We have full crowded houses, but we don't have a lot of cats coming to hang out,” Marriot said. “The good people stay home, and when people stay home, they remove themselves from the benefits of community. If we're going to have a mentorship cycle that works for our community, it requires up-and-coming young musicians to come to the jam session, but also it requires older, more veteran musicians to show up as well.”

Villafuerte, months after her discovery of the Fellowship, attends whenever she can. She never performs, but she’s always watching. On this particular Monday night her chosen dad is sitting next to her, just as stunned by the energy as I am. “He said [recently], ‘Michelle, I don't think I've ever seen this many people of your age who are so into it,” she recalls. “And I was like, ‘Yeah. I love this place.’”

Image Captions/Credits

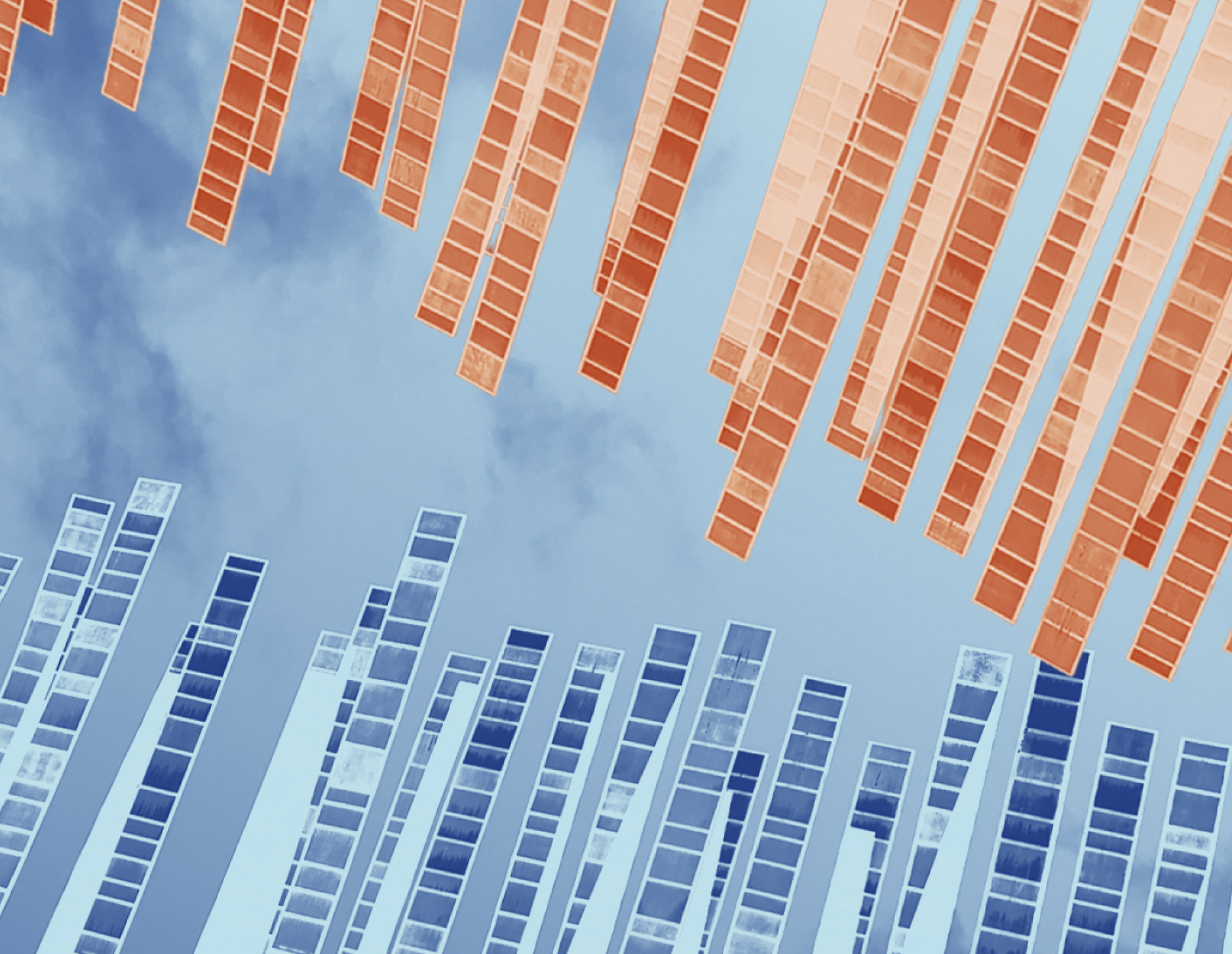

February 10, 2025. Thomas Marriott (trumpet) and Tim Kennedy (piano) at the Monday night jam session

February 24, 2025. Thomas Marriott (trumpet) and Michael Glynn (bass)

February 10, 2025. Thomas Marriott (trumpet) and Tim Kennedy (piano) at the Monday night jam session

March 21, 2025. Roy McCurdy Quintet: Marc Seales (piano), Jay Thomas (saxophone), Michael Glynn (bass), Thomas Marriott (trumpet), and Roy McCurdy (drums)

March 1, 2025. Roger Humphries (drums)

December 7, 2024. Kelsey Mines (bass) and Elsa Nilsson (flute)

.jpg)

.jpg)