On a warm summer afternoon in August, I made my way to Brandyn Callahan’s studio. Situated in what was formerly the Immigration and Naturalization Services building and detention center, the space still holds an intense quality in its new life as a large artist enclave. We sat down and drank Sapporos from ornate glasses (made by him, of course), and our conversation meandered from the beginnings of his creative journey to the technicalities of glassmaking as a material science.

In a craft so ancient, how does an artist expand their frontiers? Callahan’s answer: experimentation, collaboration, and pursuits of curiosity. He reimagines the bounds of glass with the incorporation of other materials, experimental techniques in the hot shop, and new technologies (in one case, a $30,000 Apache attack helicopter camera). His work is born from the simultaneous methodologies of an artist, craftsman, and experimentalist, and this conversation gives readers a glimpse of the fruits of such a convergence.

***

Brandyn Callahan: Making things with my hands was my childhood. Both my parents were working, so I spent a lot of time with [my grandparents], and my grandpa had a big garage shop. I mean, it was giant. It's funny, I look back like, “Oh, it was so sketchy.” He was like, "Here's a benchtop grinder. And a wire wheel. And you can polish nails.” Things were shooting off. (Laughs) I'm just sitting there at six years old … I would never put a six-year-old in front of a bench top! But yeah, making things, and my mom was really creative. She was always taking classes: plasma cutting, stained glass, or welding, things like that. She started taking some glass courses, stained glass at a community college. And so one summer, when I was young, we started fusing some glass things — and I realized that it was an instant A for book reports. You're like, “Oh, I made this fused glass panel that has all these little details that represent the book’s themes.” Instant A.

Shreya Balaji: That's so funny. But fair enough, what other child is fusing glass for book reports? (Laughs)

BC: Right? In high school, I found glass blowing for the first time. I was immediately entranced. I would just sit and melt glass rods over Bunsen burners. I had an art teacher, and her former student was working at a glass shop. She connected us. After school, I would get to the studio and hang out with a bunch of 30-year-olds making stuff and drinking beer. After I graduated, I was like, “I want to become a glass blower. I want to spend the rest of my life with this material.” College was expensive, and I can't afford it. So I was like, “Well, how about I just start working?” Try to get in somehow. I'd start showing up at studios with a box of cookies — that got me into every door.

SB: Always cold call with a box of cookies.

BC: Seriously! I had people tell me the only reason I’d get called back is because I brought cookies. So I started walking into studios in Portland. Can I sweep floors? Can I clean bathrooms? Can I do anything? Just watch and help? I kind of made myself an apprenticeship. Fairly early on, it turned into finding jobs that nobody else wanted to do. Depending on the studio, every night, or once a week, you fill the furnace up with all the raw materials. Usually, that's a shift at 11 p.m. to 1 a.m.

SB: With something so time-consuming, how is that labor managed by individual artists or the studio as a whole?

BC: A lot of times, it's a team sport. At the very least, you have one person helping you, but a lot of the teams I've worked on had three to five people working on a single object, very intensely. Have you seen The Bear?

SB: Yeah.

BC: It feels like that. That intensity. Everyone's here. There are hot things. You're constantly in everyone's business. It's part of the experience.

SB: What builds that culture? The material?

BC: Yeah. In some ways, it is the material. It demands immediacy. Sometimes when talking with folks, they'll be like, “Wow, how long do you spend on that?” And it’s 40 minutes. But it's every ounce of focus for 40 minutes. There's something for everybody to do, and yet almost all done without talking about what you need. You know where they are in the shop, you know what they're doing, you know what's happening. It's like a dance.

SB: That’s amazing. And so physical! There’s some physical and mental synchrony that has to exist for this.

BC: It's a very physical craft. There are actually certain things that, because I have weird, super long, gangly arms, I have a lot of leverage to lift large pieces. So those became my niche. You come to a place like Seattle, and everyone is so talented and everyone has incredible skills. And you're like, “How do I find a niche? How do I find things that set me apart as a commodity in working for other people?”

SB: For sure.

BC: Plus, I felt fortunate that I was able to work with a lot of really great folks, and very diverse kinds of work, too — from solid sculpted, massive figures that are anatomically accurate, to very whimsical things, blown work, work for designers, work for architects. And I do a lot of weird experiments …. What happens when we do this? What if we use this material instead? A lot of the work that I find interesting is combining glasswork with other materials. At the end of the day, the concept and what you bring to it are what give your work value, as opposed to the raw material and the craftsmanship. Because glass has such an incredible history — it goes back 5,000 years — it's really hard to make something out of glass that hasn't existed before. There have been so many times where I think I have an idea I haven’t seen before. And so I try to figure it out and play it a little bit and make it. And then you see something like it in a museum, and it was made in Egypt 3,000 years ago. It's so funny.

SB: Isn’t that kind of special, though? Like, you and someone else, separated by centuries, had the same idea.

BC: Yeah, exactly. I love that too. There's kind of like a timeless beauty that exists. As long as you're not knocking off somebody. It's too small a market to try to do that.

Part of my practice now is working as a translator between the material and ideas of architects, or designers, or artists, or even myself. It's really interesting when you bring other materials in the mix, because they have their own traditions, their own histories, and people that work with them. Copper was one that I started with. Glass and other materials typically don't work well together in the hot shop because, as it cools down, glass expands and contracts at a very specific rate. If other materials don't exactly expand and contract at the same rate that it does, they crack. But copper is soft enough that as the glass cools, it can move the copper with it.

SB: Very interesting! I’m sure the process of discovering that would’ve been super cool to follow.

BC: And that’s the thing about handmade work. There are a lot of things that students make, you know, whether they're young or they're new to a thing, that have a lot of soul. I still have my first cup that I ever made, and I love it, because it's so shitty.

SB: Is it here?

BC: Oh no, it's at the house. I do have the first goblet that I ever made.

SB: That'd be cool. I wanna see.

BC: Okay. It's so bad. It's so bad. Oh, my God. But, you know, I had been blowing glass for like two months. (Bring the goblet over) Oh, my God, it's terrible. I mean, sorry, I shouldn't say that. If you were only judging things on a craft perspective, it kind of leans, and it's kind of what we call “chuddy.” And that's like the heart of it, you know? A friend pointed out to me recently, “Brandyn, you couldn't make that now.”

SB: Even if you tried?

BC: Yeah, it's a time capsule of a period of time and where I was in life. I've spent a lifetime practicing these techniques to make very delicate objects that my hands know, and now it's hard to get back to a state where you can unlearn that… there's a beauty in the beginner that you can appreciate.

SB: The humanness of the person who made it is translated to the object, for sure.

BC: I love classical music. You have to spend an entire lifetime getting incredibly good, and then figure out how to forget some of that to find yourself, because you've ironed out all the character. So it's the same thing with objects.

SB: I know, that's why I love going to karaoke with my friends who wouldn’t describe themselves as singers. When I hear them, it just has this quality, like I know you never sing in front of people, and I feel so charmed by your voice because I can hear that. You know?

BC: (Laughs) It's not about being good; karaoke is a good example. Good doesn't have to do necessarily with vocal skills or range or your ability to nail a note. The whole idea is to sound shitty, belt it, throw yourself into something to get all the energy out.

SB: Totally. Okay. Now, a more future-oriented note…

BC: Oh boy.

SB: What do you feel is the future of glass from your own interpretation? A craft that has been around for so long, lasted for so many centuries, what's its place in the modern world?

BC: I think the future is collaborative. I think this romantic idea of people just sitting alone, making things, and then coming to a museum, selling for a million dollars, and going off in the woods — that doesn't exist. Finding new partnerships, new avenues, and being open to change. For me, a lot of that is trying to lean into new technology and understanding how it can change our understanding of the material and what is possible.

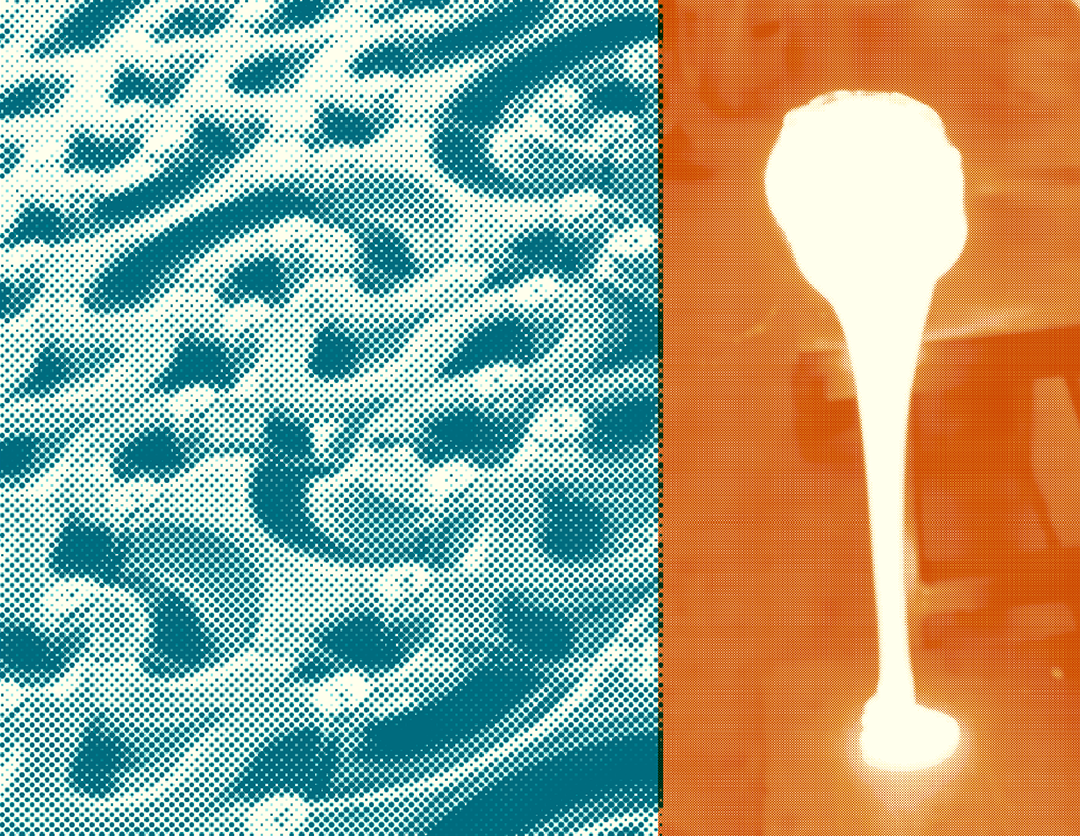

SB: Speaking of new technology, I want to talk about the thermal imaging project you did with Ethan Steinman. It was so cool to me; it had a futuristic feel… something about the fact that glass requires massive amounts of energy, something I associate with intensive tech processes.

BC: Yes! [Ethan] reached out to FLIR, who makes cameras for Apache attack helicopters and the U.S military. They said they'd lend us a $30,000 camera, so we went around and filmed all kinds of different processes in working with glass. So much of this craft is not data-based, it's intuition and superstition-based. There are a lot of people you'd ask when you’re learning about glass blowing, “Why’d you do that? How does it work?” And there's kind of an interrogative process there that doesn’t have much information to back it up. So we wanted to see if we could actually get data and see what is happening physically when people do a weird little move.

Back to what is the future… I think it's trying to honor the past and learn from all the things that have been made before, but also ask a lot of “what if?” questions. That’ll give us more life.

.jpg)

.jpg)