Whether imagined, remembered, or dreamt, narratives can be quite literally embedded into materials. They infuse a material with spirit, inspiring those who create from it. When you enter an unassuming, utilitarian structure along the east edge of Seattle’s University of Washington (UW) campus, the potent scent of wood creates an invisible threshold that wraps around you, inviting you to breathe it in with attention and curiosity. What is stored there in neat stacks is still recognizably raw wood. Elm, oak, maple, walnut, and cedar logs are stacked between evenly milled scraps. Their cracks, knots, burls, rot, hieroglyphic insect tracks, discoloration from lean water years, and slow, patient growth reveal their histories. This remarkable trove can be found at UW’s Facilities Management Department. Well organized and painstakingly tagged, the salvaged timber invites creative reuse. Its existence reflects a fortuitous nexus of urban forestry, resource management, architecture, design, and craftsmanship. How did this happen?

Over 12,000 trees at UW are tended by staff as a part of campus grounds management. Urban foresters from the School of Environmental and Forest Sciences monitor the trees’ health and viability. Campus development alone impacts this tree community. Combine that with death by natural causes—those casualties were historically chipped for use in campus landscaping. But when, in 2009, a massive elm in front of Gerberding Hall fell victim to Dutch Elm disease, UW Facilities and Grounds Management, led by Ed McKinley, was spurred to take a new approach. They didn’t want to see such a majestic tree end its life as wood chips, but they lacked the infrastructure and the tools to handle or store any salvaged trees.

Fortunately, after receiving a grant from the Campus Sustainability Fund in 2016, Facilities and Grounds was able to invest in a mobile sawmill for breaking down the trees and a solar kiln to season the timber. Today, dozens of planks that were once part of the university’s mature tree canopy await new form, new life, and new purpose in the Facilities storage space. The inventory includes Douglas fir, Western hemlock, Western red cedar, elm, oak, madrone, cherry, Western walnut, and maple. The reclaimed trees are cataloged on UW’s online salvaged tree map. Each dot on the map details a tree and its catalog number, species, source location, availability for use (or how it was reused), and where the final project is located. Photos of each tree prior to felling fill out the profile. The heritage and legacy of each tree removed since 2009 is documented with care and attention, so no tree is ever lost or forgotten.

This reverence extends to the handling of the planks after they are kiln dried and milled. Cabinet makers working in UW Facilities speak in an enamored tone of the material gleaned. With pride they share the corner of the shop where plaques are stored and slabs are available for use as conference tables and benches. Each plank bears a uniquely inscribed aluminum tag identifying the species, location, age, and date harvested. Each plank, up to 6 inches thick and as wide as an average person’s stretched hands, makes its own history visible.

To demonstrate the creative potential of UW’s trove of salvaged wood, a ten-week, interactive course offers students in UW College of Built Environments’ design-build furniture studio the opportunity to transform these precious trees, once destined to be landscape mulch, into objects with purpose and meaning. This hands-on course, open to architecture and landscape architecture students, immerses students in cyclical reuse and material revival. The studio reflects a materials-focused collaboration begun in 2022 by UW furniture studio professors Kimo Griggs and Steve Withycombe. It brings together UW’s Salvage Wood Program, its Grounds Management and Facilities Construction Unit, and the College of Built Environments. Hatched in conversations among crafters at a Georgetown brewery, this pilot program connects people across academic levels, departments, and disciplines, inspiring them to explore poetic, expressive materiality and harness the power of reuse to support, enhance, and influence the design process and production of functional objects.

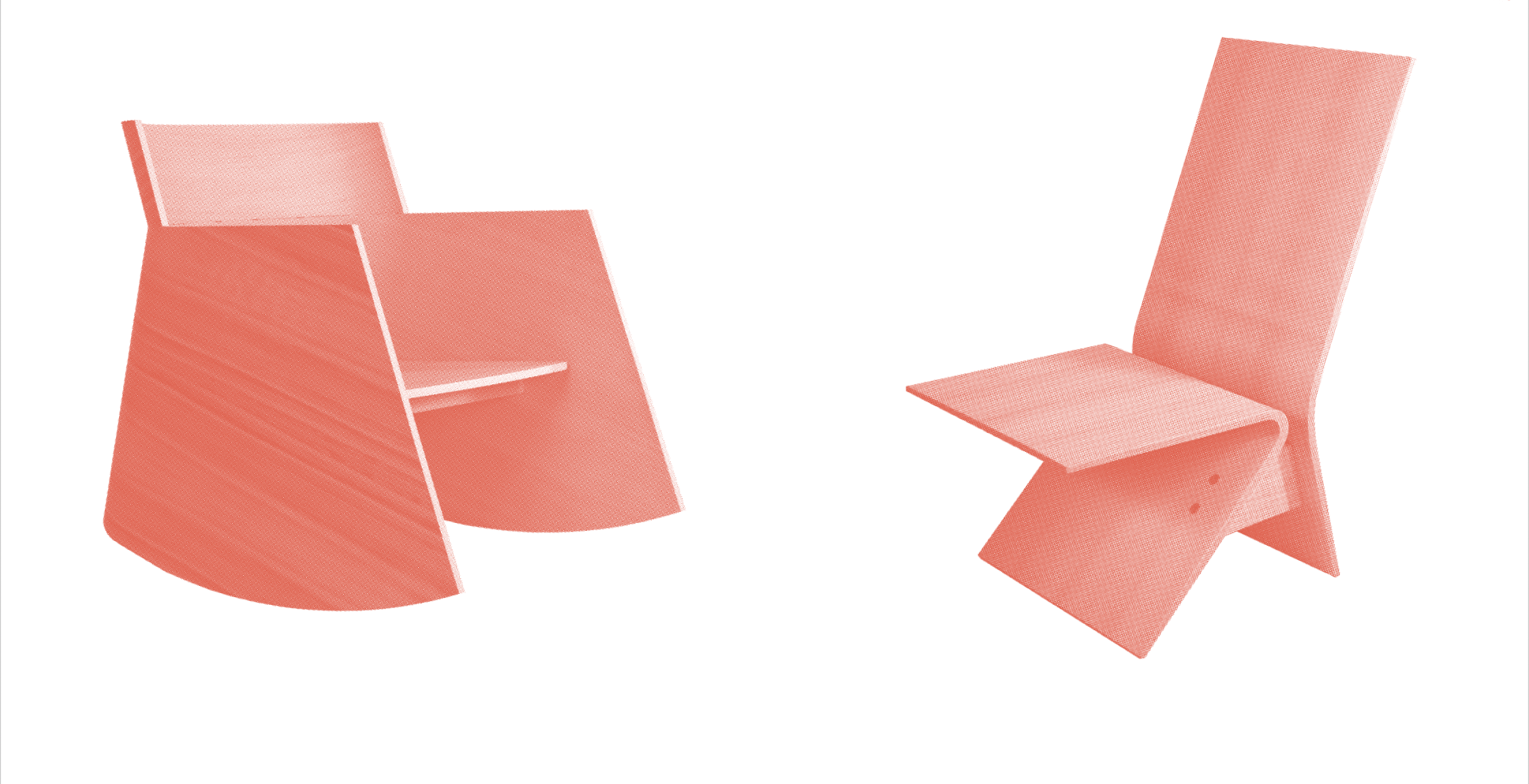

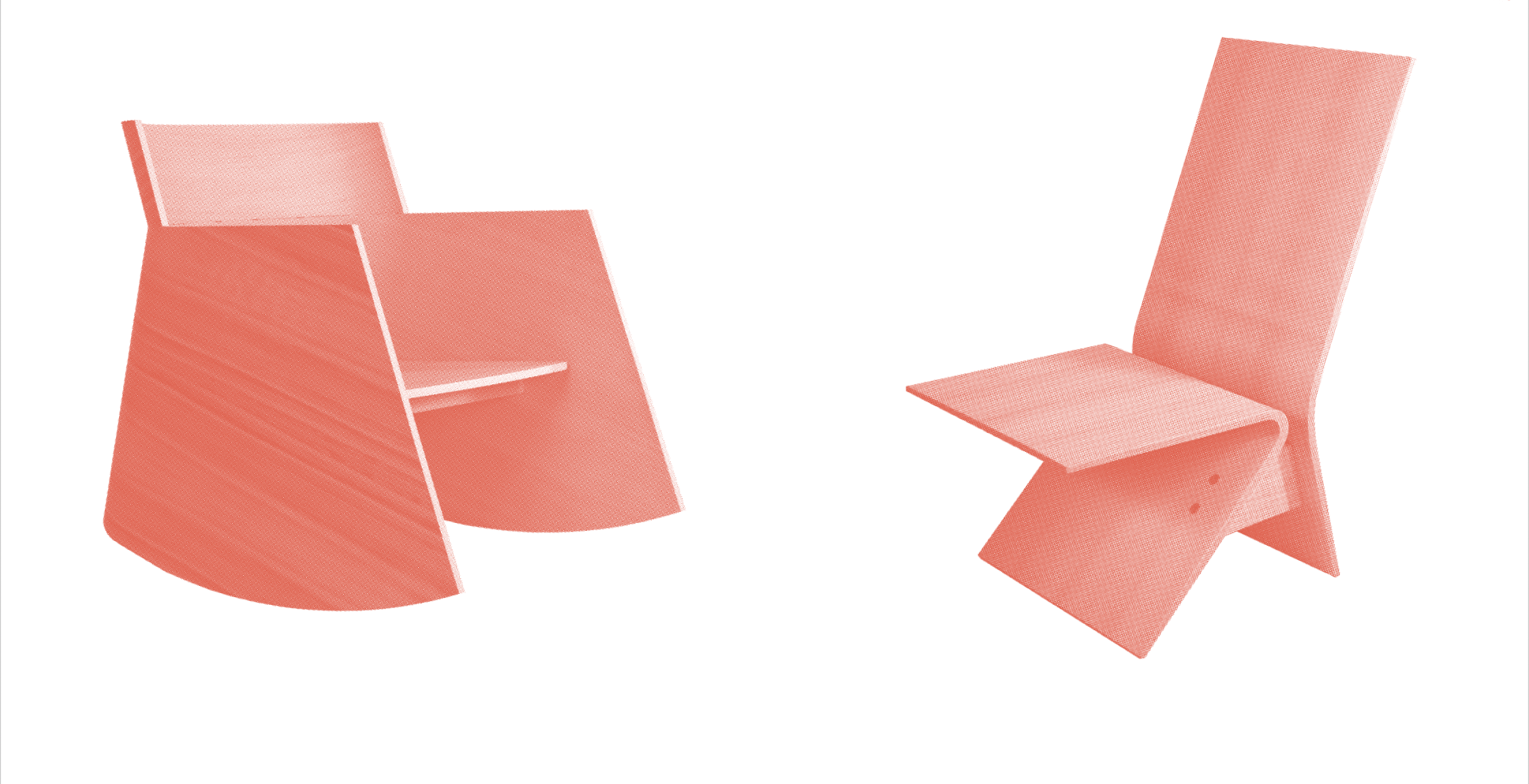

Students in the ten-week course begin by working in drawings and small models, then they make full-scale mockups during design development. Salvaged timber is preselected by the professors and then purchased and provided to students free of charge. The physical attributes of the salvaged planks lead to a kind of material alchemy, enabling the students to experience and explore wood in a more intuitive and imaginative way. Once “matched” with their planks, the students come to understand the narratives of the trees. It is in this relationship building that the life of each tree influences the process of design and making. Characteristics and imperfections, curving growth patterns, and splits give a leg or armrest a shape that otherwise might not have been considered. This kind of material influence on the final product resonates more deeply than a shopping trip to the lumber yard. Taking the experience of furniture design-build beyond a conventional understanding of wood as material, the story of the tree embeds itself in the form and meaning of the finished object. Truly bespoke, transcending practical and commercial considerations, the studio’s creative output—chairs, tables, benches, and cabinets of curiosity—descend from living trees. And their designer-makers value this legacy emotionally, environmentally, and materially.