“When abstraction sets to killing you, you’ve got to get busy with it.” – Albert Camus

***

This quote has appeared to me in various contexts and sources so many times that, at this point, it and its meaning can no longer be abstract. Taken from the 1947 novel The Plague, Camus’s words unsettle with their cool remove from any certain meaning because abstraction is, essentially, a concept without content. Its imminence lies in its constant change, remaining outside of time and place, producing a continual awareness that a vague something just beyond your reach could actually reach you and cause the demise of some or all of you and your reality. Even if it were to find you, the analgesia of indifference, to which modern human beings are prone to enjoying, would render the occurrence as a disturbance to be endured more than a crisis to be confronted. By the time we could be bothered to move, it would be too late.

This individual and societal tendency, of course, is hardly revelatory anymore. While The Plague points to disturbingly brutal events, namely the Nazi invasion of Europe, as allegorized through a quasi-fictional cholera outbreak, the novel’s sociological and philosophical themes of detachment and alienation find resonance in a less outwardly dramatic yet no less seismic shift in contemporary society: the inescapability of technology. Since the Industrial Revolution, more than a few authors, philosophers, and theorists have described how the creep of technology has irrevocably affected the ways in which we think about and relate to the world, extending and augmenting our human sensory abilities until digital technologies became the very structures of our perceptions. The line has been blurred to the point that there is no longer a world that exists outside of technology. Our insatiable appetite for stimulation is matched only by our desire for control and comfort, resulting in a reliance on technologies whose purpose is to reveal to us the nature of our world.

But what of the world, or technology, do we understand with any substance? The devices that act as our perceptual and interpretive proxies are fantastically complex and surely not neutral; yet, we plunge further in, the problems that our existence has created having long outstripped our human capacity to resolve them. Consider Google Earth, a tool so powerful for visualizing and measuring our world that “truth” seems to be self-evident in its commanding views and emanates from the software’s name: “Earth” rather than “globe” is purposeful; the latter refers to modeling or mapping, both understood as abstractions of a real thing. Even the operations of numerous aerial sensing apparatuses, relaying geographical information to automated servers to create a seamless, high-resolution visualization of the Earth, hardly seem questionable when there is the thrill of being virtually anywhere in the world, all from the convenience of your living room.

Armchair travel has existed for almost as long as photography has. Monuments and ruins were an early focus of photographic practitioners, the advent of the image coinciding with nineteenth-century preservationist movements that sought to construct notions of patrimony, historical heritage, national identity, and imperial mission. Reproduced as prints and postcards to be consumed by scholars, aspiring future tourists, and citizens back home, these visual testimonies of domestic territories and the cradles of ancient civilizations contributed to the formation of our collective imagination and the sense of an overarching view of our world. As photographic technology developed to be more convenient, populations also became more mobile, and more sights were chronicled and shared. Prior to digital platforms, our perceptions of places never before visited were a mosaic of cultural memories, books, maps, and anecdotes or vacation photos from acquaintances that were synthesized into a form of precognition, an image of reality that would, perhaps, one day find recognition in a snapshot we would make exactly there, abstract knowledge aligning with our experience. For images to be made of the world, we still had to go out into it.

Technology has now made all aspects of life visible to us at any time, but the oversaturation of media and information has not brought the world any closer to us, nor have we come any closer to it. Not only have people transformed our entire world into images, but the world is also capable of creating images of itself. The power of the human imaginary has been eclipsed by that of machines, which continually map and remap our complex visual domain as a remarkably consistent and universal field. Google Earth shows us everything in astonishing detail, but what can we know when the appearance of our environment tells us so little about its meaning and functions? Perhaps there is a clue in the algorithmically assembled forms that lay motionless and dispossessed, occupying a world conspicuously devoid of human presence.

Born from observation, this planetary double paradoxically sits in a new beyond unaffected by observers, at least conscious ones. At a distance, depictions of earthly objects and spaces are passable as representations of our world, but upon approach, reality retreats behind angular distortions and blurred details, remaining a promise waiting elusively on the horizon. In its continual slippage between semblance and nonresemblance, the object challenges meanings around use-value and form itself. Without apprehendable things, all we are left with is vague effect.

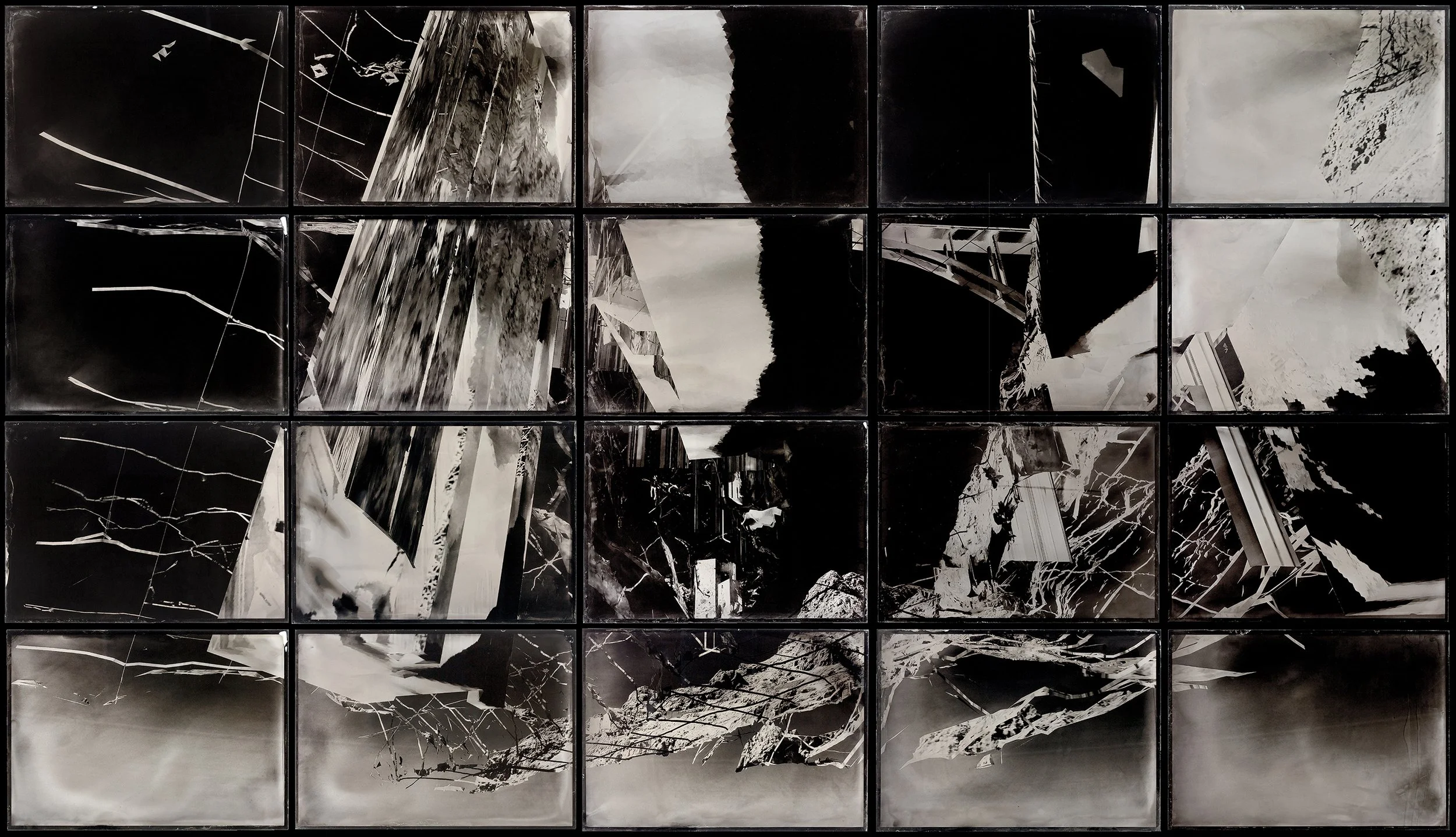

Engaging with this immaterial, networked landscape constructed from billions of images, material photography possesses a distinctive capacity to enter into a dialectic with algorithmic erasure. My series Ontic Glow combines two unpredictable processes: wet plate collodion and machine vision. Irregularities inherent to the photograph’s physical chemistry interact with digital artifacts generated by the computational operations of abstraction and reconstitution, while the direct-positive tintype images raise and blur the distinction between the indexical photographic reproduction of reality and the generation of pictures without a discrete referent.

Google Earth is situated like a para-site over the reality we occupy, taking everything as its frontier. The omnipresence of the invisible eye of technological surveillance is as oppressive as the relentlessly blue, spotless sky, always set at solar noon. It is tempting enough to see the world’s treasures, the places that leave one without words, but asking Google to show us what to know before we see it for ourselves so that everywhere is familiar yet estranged is precisely the technological not-thinking that produced this very situation. The only real option is to stray because the alternatives are desiring, belonging, or declining, all of which are anticipated moves here and would not allow technology to condition or reveal something about our desires and their object. Walk through immaterial thickets and cut across highways to move away from the banality of (former) population centers, already progressing in the machine’s imagination, constricting to produce representations that, while technically more accurate, are less moving as projections of something other than what is already known. Look for the last thing anyone would want to look at. The peripheral terrains, not yet of a high enough fidelity for true commodification, are the last refuge.

Industrial spaces and energy infrastructure are alien forms in an alienating world, postindustrial-era ghosts representing the pirating of natural resources as well as the world’s appearance being mined and extracted. Walls and topography are nothing more than surface skins that hide nothing and everything, supported by the substructure of a universal mesh through which the cosmos can be glimpsed. Rendered against darkness or swirling haze, the fragmented and malformed architectures and landscapes have a hallucinatory effect as they contort in space. Their uncertain status collapses time, merging the past and the future in the present moment.

Reified as unique, handmade photo objects, the spaces and places depicted become artifacts retrieved from the ceaseless torrents of information, more real than before in their unrepeatability and complicated by the question of our human relationship to this thoroughly unhuman world. When assembled into grids with open-ended aspect ratios, the tintypes form maps without territories, becoming endless panoramas of information that reflect our inability to locate ourselves in a simultaneous and aspatial environment. The photographic framing of these encounters and occurrences emphasizes their monumental impermanence, their unraveling signifying that these structures are nothing more than representations of representations. They are conceits that evolve through data and information that may or may not be directly related to any given site.

There is a sense that something has been lost here, but what exactly is it? The wild unraveling of digital structures, which vaguely correspond in space and time to our own existence, exposes their essential nature: the instability of their existence, a lucid view that is hardly tragic. That they may ultimately be condemned to become well-behaved architectures sounds more senseless and sad. There is shared ground here found through sympathetic imagination, which, absurd as it sounds, comprehends that our technologies oppose the aberrant and unpredictable. We may have already become inured to the ache of alienation from our sensual world or from one another, but we can still recognize it in digital visualizations. The world is what we see, and we must learn to see it.