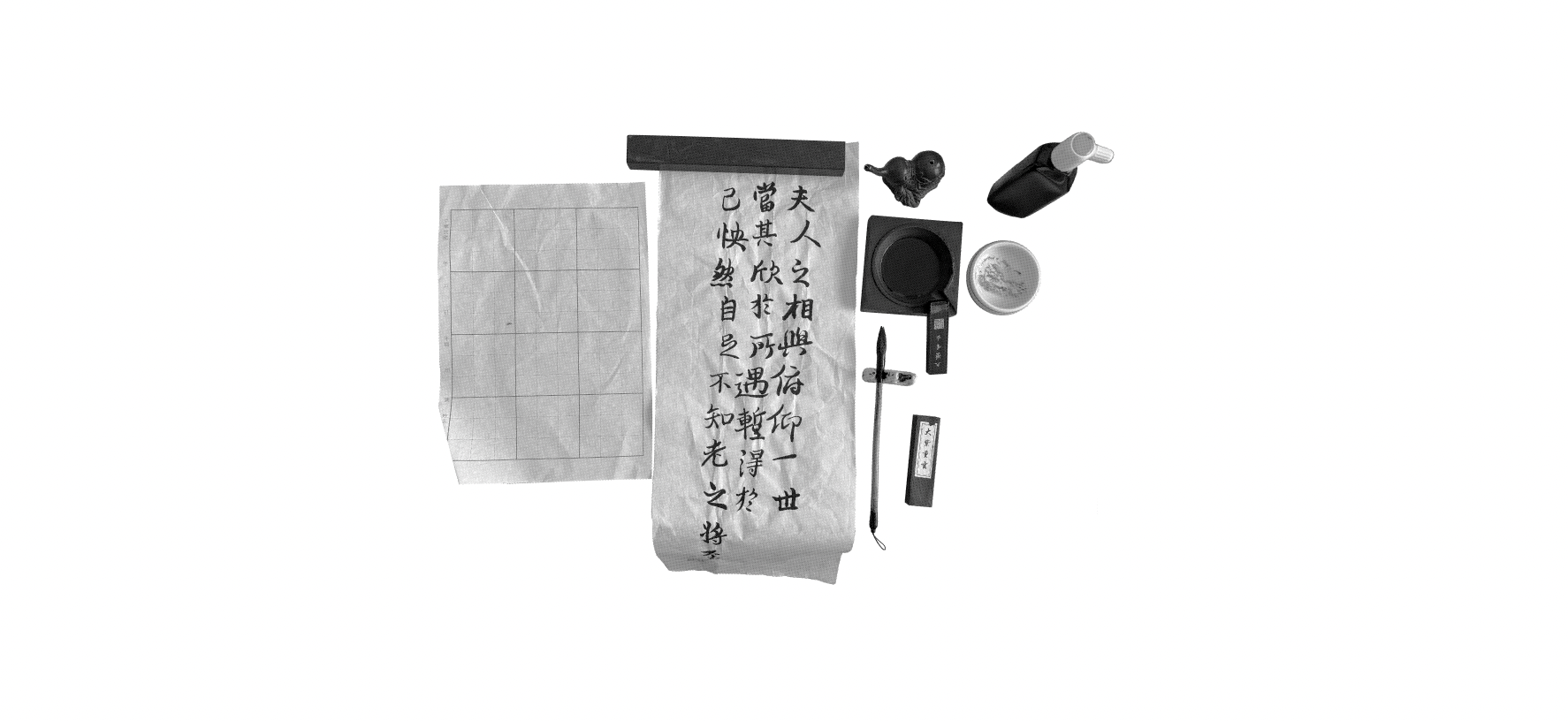

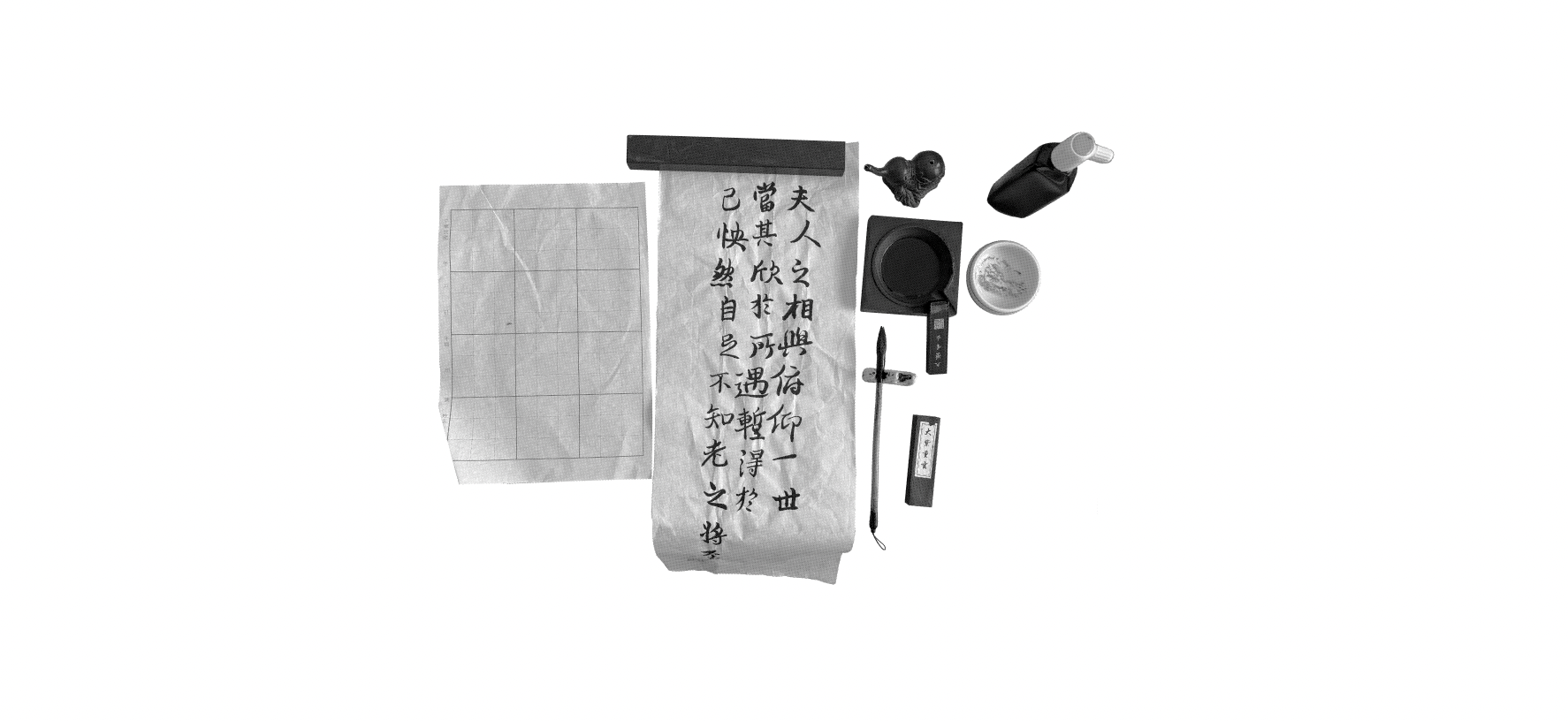

As both a literary and visual art, Chinese calligraphy makes a daunting set of demands on anyone who dares to fully commit themselves to its practice. Most obvious, one must possess a sophisticated understanding of a rich literary body of work that stretches back thousands of years. This was much easier before the distractions of our digital age arrived. Fortunately, the physical materials we used today for calligraphy would be recognizable to practitioners from a millennia ago. Called “Four Treasures of the Scholar’s Studio” wenfang sibao 文房四寶 , these are bi 筆 brush; mo 墨 ink; zhi 紙 paper; and yan 硯 inkstone.

Unfortunately, these treasures present a challenge on an immediate, material level. The brush, ink, and paper are highly sensitive to the slightest change in movement, pressure, and moisture. Thus, every nervous wobble, uncertain pause, and wayward brush hair registers immediately on the paper. There is no going back to fix, no erasing. To produce even a somewhat beautifully shaped dot or a steady line requires many years, and many tears. These materials seem purposely designed to stymie those who want to write immediately and reward only those committed to many years of practice.

In the practice of many arts, once the initial stage of euphoria with tangible progress subsides, the subsequent outlay of time required to ascend to the next level of mastery deters many people from continuing. In music, learning theory and a repertoire of standards is necessary before one can break the rules and improvise as a jazz player. Similarly, in calligraphy, one must first practice basic strokes and develop fine motor control through the systematic copying of model characters by master calligraphers and various scripts—seal, clerical, standard, semi-cursive, and cursive. Only after reaching a certain level of competence and control over materials is it possible to create one’s own signature style.

Mastery of mo 墨 ink, is especially difficult if you decide to hew to the old ways and grind your own. Traditionally, ink is made of animal glue and soot produced from burning wood, which together are then compressed into an inkstick. This type of ink is produced via a time-consuming process whereby water is added to yan 硯 inkstone, and the inkstick is rubbed against the inkstone’s hard surface. The ink is water resistant and quickly dries to a permanent matte finish. In early times, those wishing to enjoy the pleasure of writing poetry had to first face the drudgery of grinding their own ink.

Taking time to grind ink reminds me of those hallowed moments before guitar practice: I pluck a string, listen intently to each pitch, and make minor adjustments until the pitches resonate in harmony. Time stops and suddenly everything is luminous again. Just as you cannot make beautiful music on an instrument that is out of tune, neither can you write beautiful calligraphy with hastily ground, watery ink. My students sometimes ask, “How long does it take to grind enough ink? How do you know when it is ready?” I usually respond that it takes time and experience, as each inkstone and inkstick is different. In most cases the ink is too watery, and all you can do is accept the current imperfection of the state of things—your ink, the world—and just grind more.

Mo 墨 ink, is comprised of two separate characters: On the top is hei 黑 “black” and below is tu 土“soil.” Current explanations of the character for black argue that it depicts a chimney on top of a fire used for cooking 炎, which shows two fires, huo 火. Tu 土 soil, represents a chunk of earth on the ground. In explanations now unsupported by the earliest evidence but that resonate with me nonetheless, the character hei 黑 black, was thought to depict a person with dots on their face. This is a reference to the penal tattooing of criminals, one of the forms of punishment in early China. The association with criminality aside, it is the permanency of tattoos that has deterred me from deliberately applying ink to my body. That said, calligraphy ink often ends up on my hands, arms, and even face. If I am guilty of any crime, it is merely that of being loath to interrupt my practice and wash the ink off.

Most people think calligraphy is primarily a visual art, but in fact it calls on the other senses as well. High-quality inksticks are slightly heavy, but a bit lighter than a stone of equal size. Avoid those inksticks that call plastic to mind; only subpar ink will issue forth. Smell and sound are also important clues. Grinding ink emits a subtle earthy scent that the ready-made stuff lacks. Inksticks and inkstones of good quality together produce a quiet but distinct sound, reminiscent of a muted singing bowl. A more expensive and ornate inkstone is not necessarily superior to a less expensive and unadorned one. Last winter, I was foolishly taken by an inkstone with a beautiful dragon carved on top. But I found after bringing it home that its surface was too smooth to produce the necessary friction for ink. Occasionally, I will give the dragon a second chance, but that serpent now mostly stays silent, rarely hearing the gentle music of inkstick against inkstone that proceeds my practice.

When confronting unruly-haired brushes, I face the clear choice of cruelty or kindness. Either submit to the gods of efficiency and jettison the recalcitrant brush, or hold out hope for rehabilitation and continue praying to the minor god of calligraphy brushes. Extremely stiff, split-haired brushes put me in a particularly hopeless state. Instead of cooperating smoothly with its delicate paper partner, the offending brush launches a surprise attack, fatally puncturing where it should lovingly caress. Calligraphers with more wisdom and experience than me might intuitively know when a brush has no hope, but ever the optimist and always on a budget, I admit that after two decades of practice to date I have not abandoned a single difficult brush. I am in good company with calligraphers of earlier ages who accepted the physical realities of their materials, adhering to a long-standing tradition of deliberately working with broken or frayed brushes. These are moments of authenticity.

Despite its fragility in the face of brush hair aggression, paper has surprisingly become my favorite of the four treasures. To the uninitiated, all calligraphy “rice” paper might seem the same: white, semitransparent, and pliable. But those who practice know that it is usually the paper that makes or breaks the calligraphy, skill at wielding brush and ink being equal. The quality of paper varies tremendously according to price. Cheaper paper usually has a slick, shiny surface on which the ink sits somewhat stubbornly instead of being immediately absorbed in a graceful, affectionate calligraphic hug. The dots and lines thus produced do not have the clean edges enjoyed by those lucky to be brushed on the higher-quality, albeit more expensive, paper. While you can get as many as fifty sheets of low-quality paper for less than ten dollars, the high-quality paper might cost as much as five dollars a sheet or more. I tell my students that the cheaper stuff is like bland, lukewarm gas station coffee, while the higher-quality paper resembles the nuanced single-origin pour-over coffee, full of depth and flavor, that I cut from my budget to afford my calligraphy habit.

Brush, ink, and paper do not always make a harmonious combination. In a best-case scenario, they all cooperate to form a smooth, seamless finished piece. In a worst-case scenario, it’s a hot mess of blobs. Time decides it all. Time: a repeated series of moments or encounters that in aggregate make a practice, ideally daily. This requires a little discipline and a lot of obsession. Time: a prolonged commitment over the long haul, ideally years, which in my case includes the surrender of time previously lent to other commitments.

In addition to time, the greatest sacrifice a budding calligrapher must be prepared to make is space. Blessed are those calligraphers with houses or apartments large enough to accommodate a separate area for practice and storage. This is not the case for me. Rising cost of living, stagnant wages, and a tiny apartment have made it necessary to grudgingly accept my calligraphy materials as the roommate who makes a mess but never cleans up.

Paper proliferates in the abodes of sentimental souls like me who cannot bear to part with material signs of mastery. My calligraphy triumphs and failures are preserved for all of posterity on paper. Early exercises when control over ink, brush, and paper was tenuous live next to more skillfully formed characters that seemed utterly unattainable years ago, but that now appear with increasing regularity.

The meaning of the word used today for calligraphy, shufa 書法, has changed over time. Shu 書 “writing,” and fa 法 “method,” originally meant a set of writing techniques in accordance with particular standards. Only later, between the second and fifth centuries CE, did there emerge a broader notion of calligraphy as inextricably linked to individual style and self-cultivation by working with models of specific calligraphers. This concept is more closely reflected in the Japanese word for calligraphy 書道, “writing” and “path” or “tao” / “dao” shodō.

Historically, calligraphy has been, and even today remains, acknowledged as the highest art in Chinese culture and one of the most direct paths to cultivate the self. This is because the practice of calligraphy is, fundamentally, more about the work it does on you than the work you produce. One must be fully present in a particular moment and attendant to the whims of mood and wobble of hand, while at that exact same moment drawing upon a long, committed practice accumulated over years, in which improvement is incremental at best and imperceptible at worst. My early period of calligraphy practice was marked by many tears over blobs that seemed miles away from becoming dots and ragged stroke endings that showed no promise of elegance. Fortunately, over time the ugly caterpillar of frustration over my willful materials and lack of skill gradually transformed into a prismatic butterfly of gentle forbearance and faith in the process.

When I began practicing calligraphy I could not anticipate how much the insights from my practice would translate to handling difficulties in other facets of life. Struggles with finicky brushes have increased my capacity to deal with the people I used to find most difficult. Facing watery ink and knowing that all I can do is grind more has helped me more quickly extricate myself out of analysis paralysis and begin the task immediately at hand. Attunement to the gradations of paper and understanding its outsize effect on outcomes reminds me to lavish time and resources where they will make a difference.

The real work for me, though, remains learning how to be fully present and live in those long moments: simultaneously working toward mastering challenging materials through practice and also accepting that despite my commitment to mastery, there is much in calligraphy—and in life—that I cannot control.

In an age when things are available to us in an instant, it often feels futile to insist on an intimate relationship with the materials of our arts. Just as many musicians will use a digital tuner to tell when a note is in tune, so too will many calligraphy practitioners use the ready-made liquid ink from a bottle.

It’s hard to make an argument against our new god of efficiency. And yet, the antiquarian in me deeply mourns the loss of sensitivity to the nuance of materials that we fall into when we rely on machines to tell us whether a pitch is perfect or to make odorless ink that is perfectly consistent yet will fade in a hundred years’ time.

I hope there will always be just enough of us holdouts against ready-made perfection to maintain the honest struggle with the physical reality of our materials that for me is the heart of calligraphy. Let us salute those musicians who continue to wield those heavy tuning forks and the calligraphers committed to laboriously grinding their own ink. For this very struggle cultivates an attunement to the subtleness of materials, which allows for more gradations in pitches and tones and many shades of black, producing music that shimmers iridescently and calligraphy that will continue to glow for centuries. Pure presence and ultimate immortality—both. Let us then continue the good fight against the passage of our materials into obsolescence in this increasingly soulless digital age, when everything comes up on a screen with a mere click of a button and when an algorithm is behind every art we once held sacred.

For when we submit to the demands of our materials, there we may meet ourselves again.