Lauded as a panacea for sustainable architecture, mass timber’s impact on the environment has been woefully underexplored in the architectural academy and practice. The fetishization of wood as a biophilic and carbon-negative building system externalizes the widespread impacts of industrial forestry on the natural ecosystem and ignores the historic injustices of Indigenous dispossession. To free myself from disciplinary constraints and address marginalized perspectives, I turned to Indigenous oral storytelling traditions. The following six fables are meant as a moral parable, prompting practitioners to reevaluate their relationship with natural materials and their understanding of “sustainable” architecture.

Fable I: Mythmaking Cedar

It had been a very long day and The Architect was exhausted. She looked wistfully at her long-gone-cold coffee and then back at the searing light of her computer. Her eyes began to droop. The monitor seemed to ripple, lulling her to sleep. She awoke into a dream. A man sat next to her, but he was not a man, not entirely. As if two realities overlaid, he was both a man and a tree. Disoriented, The Architect only then realized they were soaring far above the treetops on the back of a massive black bird. Before she could cry out, The Raven crooned, “Join me, friends, and we’ll take a journey. You just might learn something.”

“This is The Raven of Creation,” the tree-being said.

“And who are you?” The Architect asked.

“They call me The Maker of Rich Women, The Long Life Maker, The Mother of the Forest, ts’úu to the Haida, catáwiʔ to the Coast Salish, Thuja plicata to the botanists, Western Red Cedar to the builders. I was once a man, a kind one. If someone was in need, I gave them food and clothing. When the Great Spirit saw this, he said, ‘That man has done his work; when he dies and where he is buried, a cedar tree will grow and be useful to the people—the roots for baskets, the bark for clothing, the wood for shelter’” (Stewart, 1995, p. 37).

“Now tell me, Architect, what is your origin?” The Cedar asked.

She stammered, unsure what to say. A mischievous glint shown in the eye of The Raven, weaving a trickster spell. “Oh, I’m sure you can recall something.” He conjured up a vision of a time long past that The Architect saw and recounted.

“I arrived here on a ship. I was a sailor for the English Crown under Captain George Vancouver. We came to map the coast, but before we left, we felled a log so tall and straight it could be fashioned into the masts of two fine sailing vessels.”

The Cedar chuckled. “I remember seeing you there, Architect! That Captain was an unpleasant man! In those days, The People lived in the forests. They snickered at the inept newcomers who didn’t know how to live with the land. What else do you remember?”

The Architect launched into another memory. “The lumber mills in Michigan had run dry when I heard stories about massive forests out West, trees with trunks so thick they took days to cut through. We could sell those trees back East for a hoard!” The Cedar nodded. “I met you there again as you prowled my forest. By then, many of the forest giants had already been felled. Were the stories even true? Well, they used to be.”

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

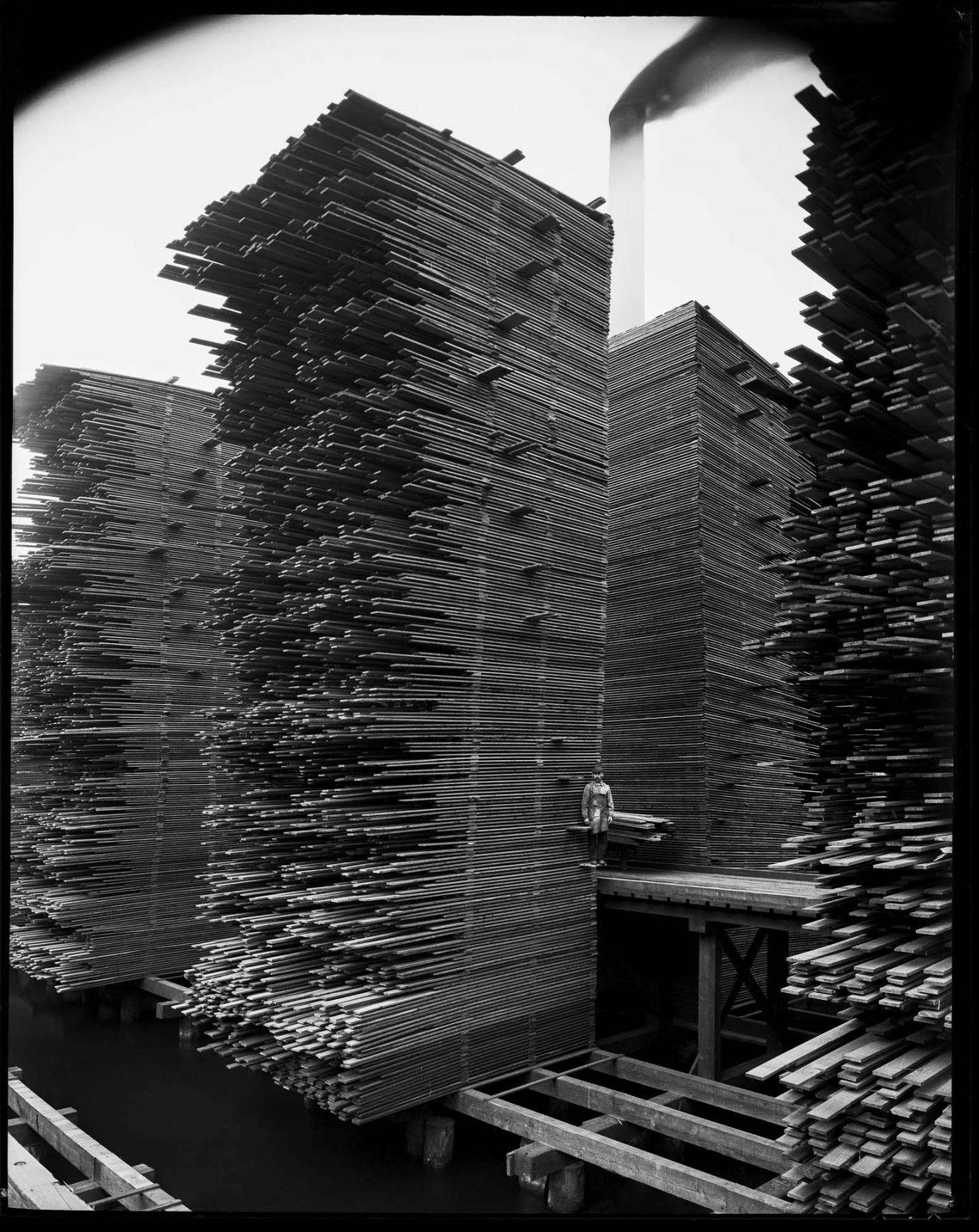

Since National Forest Service data collection began in 1964, 925 billion board feet of lumber has been extracted from Pacific Northwest forests, enough to construct half of the US residential building stock. Since the first European colonization in the eighteenth century, old growth in the Pacific Northwest has been reduced by 85 to 90 percent. Today, industrialized forestry has universally supplanted the ecological complexity of the precolonial old-growth ecosystem. The ancient forest is gone. It is not a renewable resource and can never be returned to the dispossessed Indigenous peoples who once inhabited, created with, and worshiped it.

Fable II: Growing Cedar

The unlikely trio dipped downward toward a stand of orderly trunks with sparse needles. Excitement showed across The Cedar’s knobby face. “I see young ones, Change-Maker!” The Raven let out a mighty squawk and descended so low that his talons skimmed their tops. The Cedar closed his eyes in a sort of meditation.

“What are you doing?” The Architect asked.

The Cedar shook his head in resignation. “I was calling out to my young cousins, but they didn’t seem to hear me. Even the fungal friends and animal cousins are silent.”

The Architect noticed the lanky boughs. “These trees are probably older than me! They look like they were all planted at the same time.”

The Cedar laughed. “My own seed sprouted before your ancestors sailed here. These pines are children, raised for use in your buildings. They’re carefully managed, pruned, cleared of underbrush, and spaced just far enough apart that their silent, subterranean songs are lost. They’re coaxed to grow tall and straight, and then their lives are cut short once their crowns begin to mature.”

“I read that managed forests are sustainable—that they sequester carbon,” The Architect said. “But why are there only pines? Where are the other cedars?”

The Cedar shook his head. “Young sprout, pines grow like sprinters, gulping in gas your factories belch into the sky, but they slow with age. For that, they’re slaughtered. We Cedars are an even slower bunch. As we make friends with our mosses, the Pines run past us. The loggers called our lichen-draped forests ‘decadent’ and ‘over-mature.’ Those Old Men of the Forest! Now it’s only the young, cut down when it suits the forests’ exploiters, forgetting the needs of the land.”

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Mature forest ecosystems offer vital but often overlooked benefits such as topsoil formation, habitat provisioning, and nitrogen cycling. When we use wood’s embodied carbon to offset the impacts of buildings, we fail to account for the ecological cost. True sustainability requires valuing natural materials not just for their utility to humans but also for the indispensable roles they play in supporting the planet’s health.

Fable III: Felling Cedar

Sitting on The Raven’s back, they flew over a perfect rectangle of clear-cut trees, sawed stumps left like pockmarked scars on the landscape.

“When you fell a tree, do you ask it for permission?” The Cedar asked.

“Permission? It’s not like it could answer back,” The Architect answered. As the words left her mouth, she caught herself. “I’m just an architect. I don’t cut down trees. I don’t even know where the wood I specify comes from.”

The Cedar sighed. “When a canoe maker sought my wood, he fasted and prayed for the wisdom to select a suitable tree. When a basket weaver came for my bark, she did so as a friend, with generosity of soul and respect for my efforts. She said,

‘Look at me, friend! I come to ask for your dress.

You have come to take pity on us, for there is nothing for which you cannot be used. I come to beg you for this, Long Life Maker, for I am going to make a basket for lily roots out of you. I pray, friend, to tell your friends about what I ask of you.

Keep sickness away from me that I may not be killed in sickness or in war, O friend’ (Stewart, 1995, p. 182).

“No one cultivates friendships in my forests anymore. Could you see me as a friend, Architect?” The Cedar asked. “You wouldn’t shortchange a friend. You’d give to them as much as they gave you. Reciprocity defines a good friendship.”

The Architect nodded. “You’ve certainly been a friend to me so far.”

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

It’s all too easy for architects to abstract and externalize the environmental harm of material extraction. In response to such disconnection, many Indigenous communities are turning to the legal framework of Natural Personhood, which redefines nature not as a resource to be exploited but as a community member deserving of care and respect. The Ojibwe in Minnesota have successfully secured legal personhood for manoomin (wild rice). In Aotearoa, New Zealand, the Whanganui River is recognized as a citizen, with the rights and privileges that affords. What would architecture look like if it embraced this ethic of reciprocity—treating forests not as raw materials but as living community members with agency and dignity?

Fable IV: Exchanging Cedar

The Raven cruised over the deep waters of Puget Sound. Seattle’s glass-and-steel buildings glinted in the distance.

The Cedar looked at them sadly. “I used to give my skin and heart as a gift to The People. Today, my wood is stolen and sold—looting what was once readily given. These are debts incurred against the land.” “A debt? How do I pay it back?” The Architect asked.

“What arrogance!” The Cedar said sharply. “You can only be grateful to Mother Earth for what she gives you.”

The Architect nodded, beginning to understand. “To us, wood is just something to buy and sell. What was it like before?”

“The People of this coast once lived in abundance. They had neither the will or the ability to destroy the bounty that surrounded them, so nothing was worth significantly more than anything else.” The Cedar continued, “I was valued because of the knowledge that the land itself was breathed into being along with human consciousness. Value arose from human gratitude, so The People gave each other gifts of Cedar to celebrate life. When the colonists arrived, they brought weaponry, industry, and disease. Like the forests, The People were just another resource to be exploited.”

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Many Indigenous societies did not treat natural materials like wood as commodities. In contrast, centuries of repeated deforestation in Europe transformed timber into a scarce and valuable resource. European colonists brought this scarcity mindset with them to the New World, rapidly harvesting irreplaceable old-growth forests. Their mindset of abundance enabled Indigenous societies to live sustainably with the environment. The socially constructed devaluation of natural materials persists, with destructive outcomes. To reckon with the true impacts of wood harvesting, we have to reevaluate the way we assign value to wood and timber.

The Raven flew high above the city center, the construction cranes below balanced on stilted legs.

“You’re building a home from timber. Will your family live in it?” The Cedar asked.

“No, it’s for a client. And it’s not a house, it’s an office building,” The Architect replied.

“It will serve the community, then?” The Cedar ventured.

The Architect shrugged. “It’s a place for people to work, at least.”

“When The People built their homes, everyone pitched in,” The Cedar said. “Then they held a Potlatch in thanks, and all who contributed were gifted blankets.”

"We’re being paid to design it. Isn’t that like receiving blankets at a Potlatch?” The Architect countered.

The Cedar smiled. “Would the office dwellers help you when it was time to build your home?”

The Architect pondered this. “Certainly not for free.”

“What a shame,” The Cedar said. “When The People lived here, they built great six-beam homes facing the water. The largest beam was carved with the symbols of the family that lived there. Now your homes are built of sticks, with no totem to support them.”

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In the Southern Coast Salish’s Whulshootseed language, the same words describe both human bodies and buildings. House posts are limbs, roof beams are spines, walls are skin, and sweeping is a form of healing. In a society where the family totem held up the home, physically and spiritually, great value was placed on the building and its maintenance. Claims that wood is a carbon-negative building material depend on its long-term persistence. That benefit is lost when buildings are demolished and the debris is disposed of. Sustainable architecture must be redefined to honor the full life cycle of materials, recognizing preservation as a deeply ecological act that resists the extractive logic of cyclical destruction and replacement.

Gliding east, the landscape changed. Blackened ground and split trunks of charcoal stood like silent ghosts for miles around. The Architect gasped in shock. Reading her emotions, The Cedar reassured her. “All things must eventually come to an end, but that end always gives birth to new beginnings. This is the teaching of The People.”

The Architect sighed. “The fires have gotten so bad recently,” she said.

“Humans and fire are uneasy bedfellows,” The Cedar said. “The People understood this, and coaxed the forest to burn, knowing this would fertilize the land and prevent greater infernos. They knew that fire was necessary for rebirth, and with it the Cedars thrived. It was the colonists who consigned my brethren to the furnaces of industry long ago, then you burned the carbon buried in the earth for fuel. When the past is fully consumed, your people will need the generous flame of cedar, but we will not be there to give it.” “We build our cities out of steel now,” The Architect said. “I can’t even expose the wood beams in my buildings for fear of burning.”

The Cedar nodded. “You’ve always learned the wrong lessons from the fires that ravaged your cities. Instead of learning from your mistakes, you take shortcuts and try to push the consequences of your actions onto others, even your own descendants.”

The Architect looked dismayed. “We forget that our cities are clearings in the forest. What you’ve shown me today has taught me that.”

“When the smoke rises in the fall, let that be a reminder of The Cedar, Architect. Think of my perfumed bark, pressed into incense, and fires that were never allowed to burn. We Cedar need fire to renew us, to clear the zealous pines, open our cones, and make way for our thick trunks. This is our way.” The Cedar turned to the Architect. “You asked me who I was. I’ve explained my myriad meanings to the best of my ability. But I ask again, who are you?”

The Cedar’s question jarred The Architect awake, everything she’d seen and heard alive in her thoughts. But was it really just a dream?

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Wildfires exemplify how industrial forestry practices impact our lives. Old-growth forests are highly resilient to fire, with thick bark, wide trunks, deep roots, and damp understory biomass mitigating destruction, while managed forests are more fragile. Clear-cutting and selective harvesting practices create flammable litter and irreversibly dry topsoil. The Great Seattle Fire of 1889 and the tragic Los Angeles wildfires in January 2025 both tell us to design our cities to curtail, not perpetuate, the externalized destruction of industrial forestry.

True sustainability demands more than the use of so-called renewable materials. In our current economy, the presumption of infinite growth implies infinite consumption. Treating lumber production as a climate solution ignores the reality that our planet is a closed, interdependent system, unable to support extraction at the scale of industrial forestry. Like the colonists who once stripped the Pacific Northwest of its old-growth forests, we continue to exploit natural resources in full knowledge of the damage we cause. To move beyond this toxic legacy, we must redefine how we think about sustainability in architecture. It is not an abstraction, an aesthetic, or a certification; it is care, responsibility, and reciprocity for the environment and its materials. This redefinition of sustainability begins with each practitioner confronting their own relationship to the natural world and the systems of extraction intertwined with the act of building. Writing out these fables is how I’ve started this process, and I hope it will spark others to join in. They reflect how our assumptions about materials, our methods of production, and even our means of communication can either transcend or reinforce the history of settler colonialism embedded in our industry. Only through this individual and collective reckoning can we redefine sustainability in architecture and once again revere the old growth.

Stewart, H. (1995). Cedar: Tree of life to the Northwest Coast Indians. University of Washington Press. The book includes a story told by Bertha Peters to Wally Henry (p. 37) and the Kwakiutl Women’s Prayer (p. 182).