Nina Wigfall is an interior designer based in London. After graduating from a drama and theater studies program at the University of Kent, she earned a diploma in spatial design from London’s University of the Arts and then worked with Softroom Architects and Studioilse. In 2021, she set up as a one-woman practice. Her passion is materials, but Wigfall is a designer, working on teams led by architects like Alma-nac and Chris Bagot, in concert with artists, artisans, vendors, and suppliers. She spoke over Zoom from the southeast edge of London with John Parman in Berkeley, California, where she lived as a child.

John J. Parman: You wrote that you were really busy. How is it going?

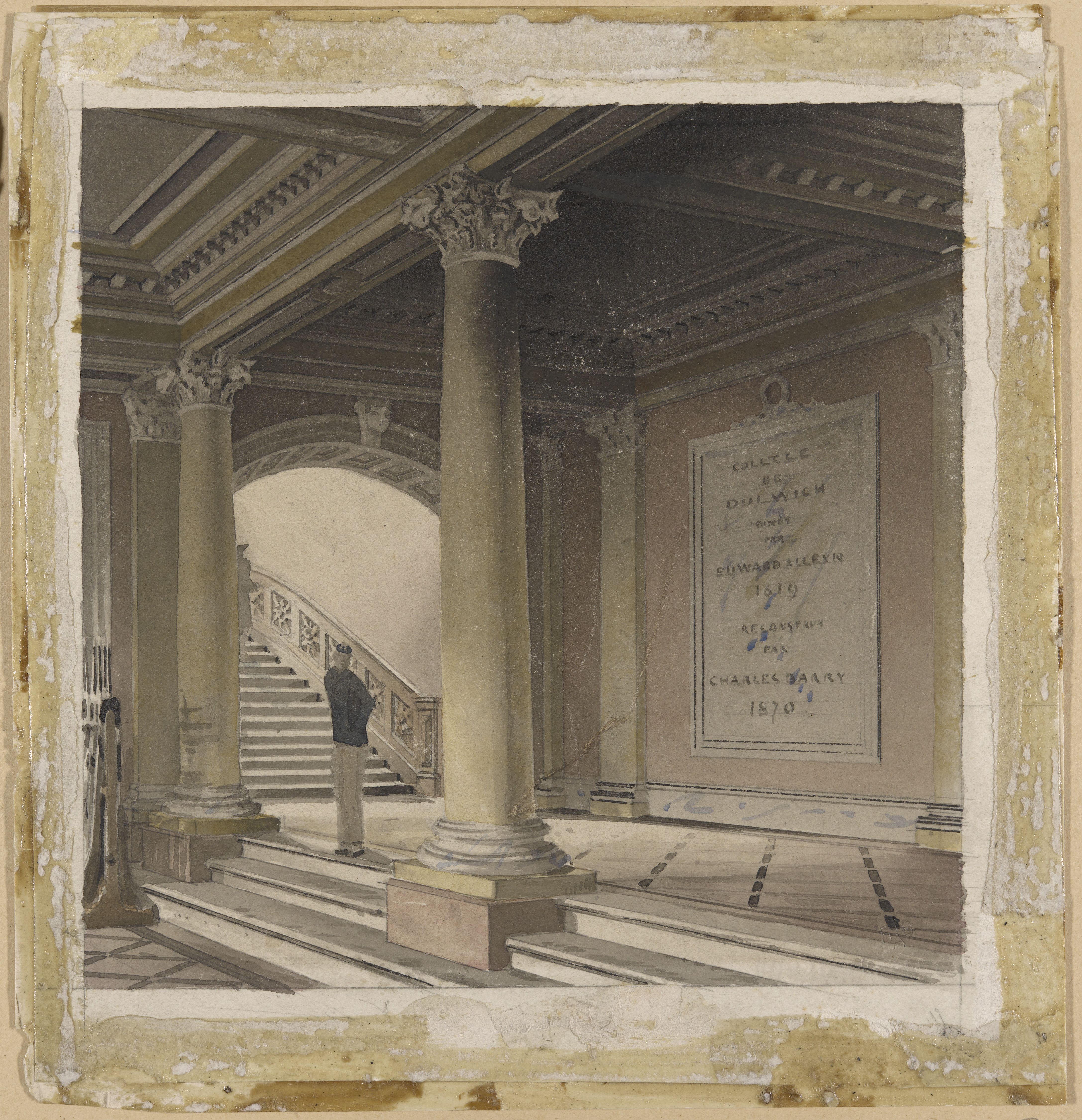

Nina Wigfall: It’s good, just very intense right now and pressured. I’m currently working on two quite big projects, both with their own specific demands. The first is a collaboration with Alma-nac working on a project for Dulwich College School. We’ve been engaged to oversee the restoration of various parts of the Barry Building, the oldest part of the school dating back to 1869, designed by Charles Barry Junior, the son of the architect who designed the Houses of Parliament. It’s Grade II* listed and extremely beautiful. Looming summer vacations are adding to the pressure. I have to finalize the specifications for all the FF&E [furniture, fixtures, and effects], which is meticulous, focused work. On top of that, I’ve got a new project to design a series of holiday cottages for a client up in Scotland, with Chris Bagot Architects. It’s at the concept stage. Chris and I go way back, to my first job at Softroom, where he was a director.

JP: Say more about your new project.

NW: The client plans to renovate a number of dwellings, in various states of disrepair, and turn them into holiday rentals. When we were brought in, work had already started on the first one, so straightaway we were asked if we wanted to make any changes while the contractors were on site. After a hasty site visit, we’re now rushing to make those changes. We’re developing an overall concept for the project.

JP: Can you describe how you work?

NW: I’m an FF&E designer—furniture, fixtures, and effects. It’s a very broad role with many facets to it. My work starts at the very beginning, when we’re coming up with a design vision for a project. That means looking at colors and materiality, furniture and lighting—all those layers we want to incorporate to make that space feel good. We work in tandem. I’ll often brainstorm and come up with an initial presentation, a concept board or mood board, while others focus on the architecture and spatial design—very much a fluid conversation, which I love.

Once that stage is done, I’ll turn my attention to selecting the furniture, fabrics, lighting, etcetera, and calculating costs. Everything has to be sampled to ensure that it meets the requirements for durability and complies with regulations, such as fire retardancy. Once it’s all approved, it’s scheduled, checking lead times to confirm that orders can be fulfilled. Only then can I take a breather, as my role is largely done until, right at the very end, I might oversee the installation and styling. It’s a hugely creative role, with an enormous amount of decision making, but it demands a very high level of attention and focus.

JP: How did you learn about materials?

NW: I fell quite naturally into becoming Softroom’s materials librarian, with a particular love for the tactical side and away from the technology. I also enjoyed the social aspect of it—the regular meetings with manufacturers and suppliers, the visits to factories to see how things were made, attending design fairs, etcetera. I became the go-to person for ideas and advice on materials, and I kept the library well-stocked and current. My knowledge grew from there. I was supported and encouraged to do it.

When Softroom closed, I offered to take the library off their hands. I’ve got some forty crates of materials, but it’s all in storage at the moment. I thought that if I freelanced with smaller practices, I could use this resource on a shared basis. My dream is to get it back in one place. I’d love now to lease a small shop where people could see and use it. People are drawn to materials, wanting to pick them up, touch them, put them side by side. It would be fun to run workshops using them, helping people design their own spaces.

JP: In your work you must encounter aesthetics different from your own. How do you deal with that?

NW: You do, for sure, and sometimes it’s nice to be pushed outside of my comfort zone. When I started out, I was helping to design the Wahaca restaurants, founded by chef Thomasina Miers. Their brand is vibrant and colorful, and we played with different patterns and materials in very fun and original ways. It was at odds with my much quieter sensibility, but it was great to train my eye and my mind in that way. You begin to spot things all over the place—“Oh, that’s very Wahaca!” Years later, I’m still doing it.

JP: What about designing in historic buildings or spaces?

NW: In Paris recently, I visited the Eurostar Lounge at Gare du Nord Station, which Chris designed with Softroom. It’s really held up, and that’s partly to do with its architectural bones. I’ve worked on projects at the British Museum, the V&A, the Royal Albert Hall, and now at Dulwich College—all great historical institutions. Projects like that are an enormous privilege but also a great responsibility. You want to bring it into the contemporary, but you’re hugely sensitive to what was there before. With Alma-nac, we’re furnishing the Master’s Library at Dulwich College, and oh my god, it’s such a beautiful space! Timber panels lined with old books, a creaky parquet floor, all this old furniture—I thought, “Don’t change anything!” We felt really conflicted. What can we put here that won’t feel too new and won’t lose that magic? It’s led us to design something quite classical. The colors—deep browns, and dark greens and blues, feel suitably traditional, whilst the furniture is quietly modern and beautifully crafted. The plan is to replace the old parquet floor, too worn and damaged to restore. I’ll miss its creaks and unevenness. The wibbly-wobbly standing lamps, which had their charm, will now stand straight. As time goes by, new layers will be added to it, of course. A floor is a palimpsest.

The presumption is that everyone tasked to redesign a space believes they’re making the right choices. Sometimes, though, you ask yourself, “Why did they do that?” The existing Lower Hall at Dulwich College is a perfect example. There are these classical columns, and in the last redesign they were painted oxblood red. It’s so heavy and oppressive! I know the Victorians liked this red, but it was a strange choice. In our research, we discovered a very early illustration of the Lower Hall in the RIBA archive. Back then it had a very light color palette, very fresh, and that informed our decision to erase the red.

JP: William Morris opposed the Victorians’ penchant for imposing their own view of what was proper when they restored an old building or interior. It’s like your oxblood columns.

NW: Change is fine to keep a place relevant, but it’s good to know how it was. Your mentioning Morris makes me think of London’s Victorian brick terrace houses. People buy them and spend a lot of money cleaning up the brickwork. I lived on one such street and I felt its history was being erased, making it look brand spanking new. Of course, it looked that way once, so it’s strange really that I was so offended by it.

JP: We expect the materiality of our everyday to have a patina to it. We want to see time around us, and buildings are markers of time in some sense. When you erase it, it’s jarring.

NW: That sense of time, or its passage, is interesting in relation to the material choices I make as a designer. It often comes up with sustainability, choosing one material over another if you know it will stand the test of time. An example is faux leather versus real leather. Many see faux leather as the more sustainable and ethical choice, yet it’s so much more nuanced than that! Real leather ages beautifully; it’s part of a circular economy, made from a byproduct of the food industry, and it can be restored and repaired. Often it looks and feels better the older it gets. Faux will never age gracefully—it rips, and before you know it, it has to be replaced. So which is the more sustainable option? The longevity of real leather argues for it, while defaulting to faux leather as the sustainable choice strikes me as tokenism. If you don’t want the real thing, then don’t bother. I always prefer to use the real material, not something that’s trying to mimic something else, like timber-effect tiles for example. They might deceive the eye initially, but as soon as you touch them, they feel wrong. The greatest gift I can give my clients is to help them make smart, informed, and thoughtful choices about materials. The way they feel and the sense of quality we unconsciously absorb from them, that emotional connection, is something I emphasize.

JP: Do questions about sourcing come up in your work—who made it and where did it come from?

NW: Most clients are concerned by how it looks and what it costs. As the one who’s helping them, there’s responsibility there for me, but I’m not working in isolation. I know my suppliers and trust them to do their best on issues like this. Whenever possible, I also source locally. With the project in Scotland, my natural instinct is to focus on Scottish craft and materials. There is fallen timber on the estate, which they’re happy for us to use. The quality of local making is really good, so the client is encouraging it. The goal is to root the cottages in their setting. This means using the local timber, incorporating textiles woven in local mills, thinking about the colors and rugged textures of the estate, and using these different elements to weave together the authentic feeling and atmosphere of that place.

JP: Where does an FF&E designer find inspiration?

NW: Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge is a really special place, filled with beautiful paintings and artwork. There are also collections of natural things, presented with such consideration and care—pebbles arranged tonally in a spiral on a table, for example, or dried leaves and bracken on a window ledge, their textures drawn out by the sun. These small details catch my eye, and they’ve inspired my thinking about how to bring the Scottish estate’s remarkable landscape in as an element in the cottages’ design and styling.

JP: Charles Handy, the late management consultant, coined the term “portfolio work” in the 1990s, giving freelancing a big boost. I did it for fourteen years. What’s your experience been with it?

NW: I made a conscious choice when I became a mother that I wanted to keep working but it was important to me to be able to drop [everything] and pick up my daughter at the school gate. Juggling work in a busy studio and fighting London’s unreliable trains ended up being too much. I was stressed and exhausted. It led me to take the plunge and go freelance. Looking back now, it was the best thing I could have done. The pandemic helped because it forced that working-from-home thing. I now have the flexibility to handle work and life simultaneously, and not feel that either is having to take second fiddle to the other. Not that many careers allow that. My work is very stimulating. I'm very lucky in that sense, too. But it did take some getting used to. It’s great when it’s going well, but when it’s slow, it's very easy to start panicking.

You sent me an article from the Financial Times about consultants who rid houses of negative energy. That’s one thing I believe, that there are these energies in the world and you have to put the positive ones out there. It’s when you do that things come. My husband Emile Rafael and I often talk about this. He’s a filmmaker, and the industry at the moment is pretty dire. He was just saying that he wants to make a music video, a self-project he’s doing for love. “As soon as I start it, I bet all this new client work will suddenly appear,” he told me. “Well, get to work,” I said. That kind of energy!